FEATURE

13 February 2019

Behind the Mac creator celebrates his literary icon

Barry Jenkins on James Baldwin, Filming Black Skin and Filmmaking in the iPhone Era

Oscar-winning director Barry Jenkins says he “stumbled into filmmaking,” attending Florida State University for some years before discovering its film school. “I went to film school right at the turn between old school cinema and new school cinema,” Jenkins says, “so we actually learned to edit films on these things called flat beds … you have to actually physically cut the film and tape it back together. So, doing that for a full year and then transitioning to what they call non-linear editing, it was shocking.

“But I took the lessons with me,” he continues. “Only make the cuts you absolutely have to make.”

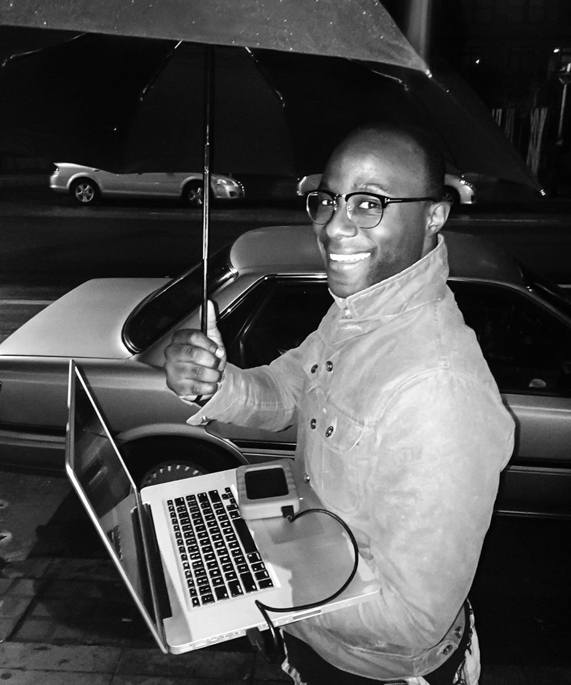

In last year’s Behind the Mac campaign that celebrates creators using Mac in their work, Jenkins is seen holding his MacBook Pro while standing under an umbrella in the rain. The director was exporting the final cut of his 2017 Academy Award-winning feature film, “Moonlight.”

Trained in traditional and modern filmmaking, Jenkins blends his craft with digital equipment like his ARRI Alexa camera, MacBook Pro and even his new iPad Pro. “These Arri cameras and the Apple platform are the two things that have helped me become the maker that I am,” Jenkins says.

His latest film, adapted from James Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk,” is a cautionary tale about black life in America in the 1970s, spotlighting the hardships a young couple face navigating a changing world around them. The novel was published in 1974, six years after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, and a decade after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Barry Jenkins on set with actors Dave Franco, Stephan James and KiKi Layne. Photo courtesy of Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures.

Baldwin’s literary tone is critical and unapologetic about his analysis of the state of the world around him. He crafts a delicate balance between the beauty and the brutality of America.

In Jenkins’s adaptation, that balance is achieved through portraits of moments shared between Tish (played by KiKi Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James), from the streets of Harlem to the West Village, to the bulletproof glass at the Manhattan Detention Complex — or the Tombs.

“My job in making this film, from the craft standpoint, from the aesthetic standpoint, was about trying to translate interiority into sounds and images, and to do so with the words of James Baldwin.”

To translate Baldwin’s words into moving pictures, Tish narrates the events that led to her and Fonny’s current status: in love, expecting and fighting for Fonny’s freedom after his wrongful arrest.

“The movie is composed of memory streams and nightmares and so how does 19-year-old Tish, how does she view Harlem?” Jenkins continues. “How does she want to remember it? And once we hit on that, that’s when the whole world opened up for us.”

“If Beale Street Could Talk” is the first English-language adaptation of James Baldwin, a prominent author on race relations in the US during the Civil Rights Era. Photo courtesy of Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” is the first English-language fiction adaptation of Baldwin, a feat with its own set of unique challenges.

“Literature is a very interior medium, it’s all about the interior voice,” Jenkins says. “And cinema, it’s about externally acting out in a certain way. You know, sounds and images. You’re not necessarily allowed to be inside the character, and James Baldwin, the power of his writing is all about the interior voice. So my job in making this film, from the craft standpoint, from the aesthetic standpoint, was about trying to translate interiority into sounds and images, and to do so with the words of James Baldwin.”

Shot on an ARRI Alexa 65, “Beale Street” gives audiences a close, intimate look at black life. Jenkins is grateful for the ability to capture the intimacies of black family and love, dreamed up by his literary icon, in such a large format.

“The history of [cinema] is all tied to 35 mm emulsion,” Jenkins explains. “These cameras now are programmable computer chips so you can write the algorithms to dictate how they behave, how they perceive light. In the past, you were limited in some ways by how certain film stocks were created and what their dynamic range was. Now, whenever we set up to make a film, we can program the computer … from scratch. So right away, we’re building these cameras to prioritise darker colours, by which I mean darker skin tones. It’s very freeing.”

Filmmaker Barry Jenkins, featured in Apple’s Behind the Mac ad, exports the final cut of his Academy Award-winning film, “Moonlight.”

Beyond the new cameras, filmmaking still requires a bit of magic. Enter the editor.

Joi McMillon is a longtime Jenkins collaborator. One of the two Oscar-nominated editors on “Moonlight,” she “breathes” Avid on the Mac Pro. McMillon worked with Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton to bring the film to life.

In one scene, Fonny and Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry) spend hours in Fonny’s apartment catching up, moving from small talk to something troubling for Daniel.

“It’s kind of like a scene within a scene, and they change up the lighting and the angle and so as an audience member, you’re not exhausted by being somewhere for that long,” McMillon explains. “There’s now new information in each section of that part of the film.”

Jenkins wanted the audience to feel the energy being transferred between Fonny and Daniel. A camera slides slowly between them, a progression deeper and deeper into Daniel’s mind and Fonny’s reaction.

From left: Fonny (played by Stephan James), Tish (KiKi Layne) and Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry) in Fonny’s apartment, moments before Daniel opens up about his incarceration in “If Beale Street Could Talk.” Photo courtesy of Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures.

“There’s such warmth on Fonny and Daniel’s skin and yet what they’re talking about is so dark and scary and I just love the juxtaposition of that,” McMillon says. “The way it’s shot makes you feel like you’re sitting at the table with them.”

That immersion is now a Jenkins staple. Audiences sat at a similar table in a diner in “Moonlight,” and even floated in the ocean with those characters.

Today Jenkins, McMillon and the “Beale Street” family are once again on the awards circuit. The film is nominated for three Oscars: Best Supporting Actress (Regina King), Best Original Music Score (Nicholas Britell) and Best Adapted Screenplay (Jenkins).

“Even the old school cats that are embracing these new tools … they get down and dirty digitally.”

Up next: An Amazon series based on Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad.” Jenkins jokes this will round out his artistic bucket list: “Make a movie about where I was from, and that became ‘Moonlight.’ I also wanted to adapt my favourite author, and that’s ‘Beale Street.’ And the last was I wanted to make something about the condition of American slavery. And that’s ‘The Underground Railroad.’”

As Jenkins ticks off his list, he acknowledges a new class of filmmakers he says he’s sure will lap him soon. “Even the old school cats that are embracing these new tools … they get down and dirty digitally,” Jenkins says. “Steven Soderbergh has been working almost exclusively off the iPhone for the last few years.” (Soderbergh’s latest film, “High Flying Bird,” was shot entirely on an iPhone 8 and premiered on Netflix last month.)

“You can kind of make any damn thing right now, whether with your phone or with a DSLR,” he says. “The world is a young filmmaker’s oyster.”